Politics, Governance & Regional Affairs

Ethiopia–Somaliland Deal Shakes Horn of Africa

Ethiopia’s recognition of Somaliland could have significant ramifications. Regional powers such as Djibouti, Eritrea, and various Arab states with interests in the Red Sea corridor are approaching this development with caution. Somalia, which considers Somaliland part of its territory, strongly opposes this move, fearing that Ethiopia’s support may inspire other secessionist movements and undermine its territorial integrity

Ethiopia’s port access deal with Somaliland sparks tension, marking a major shift in Red Sea geopolitics and African diplomacy.

Ethiopia–Somaliland Port Deal Sparks Red Sea Geopolitical Shift

In a historic move on January 1, 2024, Ethiopia and Somaliland signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) granting Ethiopia access to Red Sea port facilities, with Ethiopia agreeing to recognize Somaliland as an independent state.

Signed in Addis Ababa by Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed and Somaliland President Muse Bihi Abdi, the agreement is expected to reshape regional geopolitics in the Horn of Africa—a region long defined by instability and complex rivalries.

✅ Ethiopia Gains Strategic Access to the Red Sea

As a landlocked nation since Eritrea’s independence in 1993, Ethiopia has relied heavily on Djibouti’s ports for trade. The new deal provides Ethiopia direct maritime access for both naval and commercial use, a move likely to diversify trade routes and improve national security.

“This agreement is about sovereignty, development, and regional partnership,” said an official in Abiy’s office.

🌍 Somaliland Edges Closer to Global Recognition

If implemented, Ethiopia would become the first country in the world to officially recognize Somaliland’s independence—33 years after the region declared itself independent from Somalia in 1991. Though Somaliland operates its own government, currency, and institutions, it remains unrecognized under international law.

Recognition from Ethiopia could set a precedent and encourage other African or Western nations to follow suit, boosting Somaliland’s long-standing push for sovereign legitimacy.

⚠️ Tensions with Somalia and the Region

The deal has triggered alarm in Mogadishu. Somalia, which views Somaliland as a breakaway region, has strongly condemned the MoU, calling it a violation of its sovereignty.

“Any foreign agreement that undermines Somalia’s territorial integrity is null and void,” declared Somalia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Neighboring states—including Djibouti, Eritrea, and members of the Arab League—are also watching with concern, fearing the move may inflame separatist movements and challenge regional borders.

🔎 Why It Matters: Horn of Africa in Flux

This development has major implications:

- Geopolitical Realignment: Ethiopia is signaling independence from traditional port partners like Djibouti.

- Increased Regional Tensions: The Horn of Africa could see more friction as border claims and alliances are tested.

- Potential for Instability: Experts warn that other marginalized regions could pursue secession, destabilizing fragile states.

📌 What’s Next?

With regional powers on edge and the international community watching, the UN, African Union, and major global players will likely step in to mediate tensions. The outcome of this high-stakes agreement could redefine Ethiopia’s maritime future and Somaliland’s diplomatic status.

🔗 Related Reading on This Site

Elections & Political Transitions

Uganda Sets Jan 15 Poll Date

Opposition leader Bobi Wine says Uganda’s polls will test the country’s democracy amid tight timelines and alleged state repression. Analysts warn that political unrest could deter foreign investment in the oil-dependent economy.

Uganda sets January 15 2026 election date as President Museveni faces Bobi Wine in a high-stakes vote watched globally.

KAMPALA, Oct. 23, 2025 — Uganda’s Electoral Commission on Wednesday announced that national elections will take place on January 15, 2026, setting the stage for another political showdown between President Yoweri Museveni and opposition leader Bobi Wine.

The poll date, confirmed in an official statement posted on the commission’s website, starts a high-stakes countdown for Africa’s third-longest-serving leader. Museveni, 81, has ruled Uganda since 1986 and is widely expected to seek a seventh elected term under the banner of the National Resistance Movement (NRM).

A tightening political field

Analysts say Museveni’s decision to run again could deepen tensions in a country where calls for leadership transition have grown louder. “The next election will test Uganda’s institutions more than any before,” said Moses Khisa, a political scientist at Makerere University. “The stakes are enormous for both the regime and the opposition.”

The opposition National Unity Platform (NUP), led by musician-turned-politician Bobi Wine — real name Robert Kyagulanyi — says it will field candidates nationwide despite continued restrictions on rallies and alleged surveillance. Wine accused authorities of trying to “block meaningful political competition” and urged international observers to monitor the vote closely.

Economic backdrop and investor concern

The announcement comes as Uganda prepares to become one of East Africa’s new oil producers, with commercial drilling expected to start in 2026. French energy major TotalEnergies and China’s CNOOC are leading a $10 billion oil project in Uganda’s Albertine region. Political instability or unrest could delay the project’s timeline and rattle investor confidence.

According to the Bank of Uganda, inflation has remained stable around 4.7%, and GDP is forecast to grow by 5.5% in 2025, supported by construction and services. But economists warn that pre-election uncertainty could slow private investment and push up fiscal spending. “Governments often loosen spending controls ahead of elections, and that can put pressure on the shilling,” said Razia Khan, Chief Economist for Africa at Standard Chartered.

The Ugandan shilling currently trades at about 3,720 per U.S. dollar, slightly weaker than last month, reflecting increased dollar demand from importers and cautious sentiment among foreign investors.

Governance record under scrutiny

Museveni’s supporters credit him with maintaining stability in a volatile region and overseeing infrastructure growth, including new highways and hydropower projects financed partly by China Exim Bank. But critics say his long rule has eroded civil liberties, weakened institutions, and centralized power within the presidency.

Uganda’s constitution once limited presidents to two terms, but parliament scrapped that clause in 2005. Lawmakers later removed the age cap in 2017, allowing Museveni to run indefinitely. The opposition called both moves “a betrayal of the democratic process.”

Human rights groups such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have accused security forces of using excessive force against protesters and journalists. Authorities deny systematic abuse, insisting that law enforcement acts within Uganda’s laws.

Tight timelines and regional implications

The electoral commission said it will publish the final register by early December, giving parties less than three months to campaign nationwide. Uganda’s rural districts, where Museveni’s support base remains strong, are expected to decide the outcome.

Observers say the election’s impact extends beyond Uganda’s borders. The country plays a key role in regional security through its involvement in East African Community missions in Somalia and South Sudan. Political unrest could complicate joint security operations and disrupt trade corridors linking Kenya, Rwanda, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The African Union (AU) and United Nations are expected to send observer teams once formal invitations are issued. The U.S. State Department and European Union have urged Uganda to ensure “a level playing field” for all candidates.

Opposition seeks to rally youth vote

Bobi Wine, 43, remains the face of Uganda’s youthful opposition. In 2021, he came second with 34.8% of the vote, alleging widespread fraud — claims rejected by the electoral body. His message of change still resonates with Uganda’s median age of 16.3 years, one of the youngest populations in the world.

“Uganda’s young people want jobs and fairness, not fear,” Wine told reporters at his party headquarters in Kampala. “This election will define whether our nation moves forward or stays stuck in the past.”

Rising global attention

International investors and diplomats are watching closely. Uganda’s stability has made it a key partner for the World Bank and IMF, both of which resumed major lending this year after a freeze over human-rights concerns.

“Uganda matters to the region’s macroeconomic outlook,” said Mumbi Seraki, an Africa analyst at Moody’s Analytics. “If the elections trigger unrest, that could ripple through the EAC’s investment climate.”

Politics, Governance & Regional Affairs

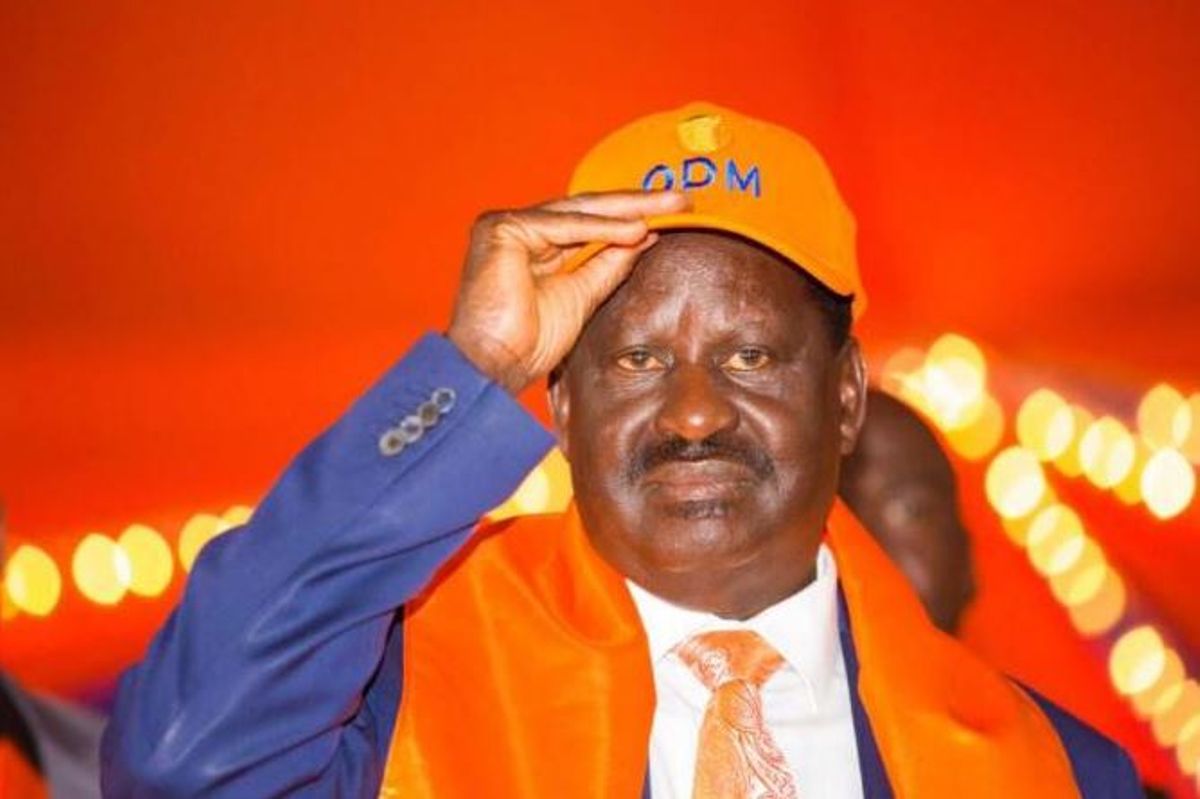

Raila Odinga’s Death Tests ODM Unity

President William Ruto pledged to preserve Odinga’s legacy within the broad-based government. But internal ODM factions are already testing that promise as 2027 draws near.

Raila Odinga’s death leaves Kenya’s ODM party battling internal divisions as leaders weigh loyalty to Ruto’s broad-based government.

Kenya is entering a new political era after the death of Raila Odinga, the country’s former prime minister and long-serving opposition chief. Odinga died on October 15 in India’s Kochi city while undergoing heart treatment and was buried on October 19 at his rural home in Bondo, Siaya County.

For two decades, Odinga led the Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) — now part of President William Ruto’s broad-based government. His passing has triggered uncertainty over the party’s leadership, future alliances, and identity in Kenya’s fast-shifting political landscape.

A Legacy That Redefined Opposition Politics

Odinga was celebrated for his lifelong fight for democracy, multi-party freedom, and devolution. He was detained three times under former President Daniel arap Moi’s rule and played a key role in writing the 2010 Constitution.

“Raila Odinga was more than a politician; he was Kenya’s political conscience,” said Professor Peter Kagwanja, a Nairobi-based political analyst. “He gave voice to the voiceless and reshaped how Kenyans think about leadership.”

Odinga’s political genius lay in his ability to transform populism into national reform. His 2025 handshake with President William Ruto created the Broad-Based Government of National Unity, a post-crisis framework designed to cool political temperatures and attract investor confidence amid rising inflation and a weakening shilling.

Power Struggles Emerge Within ODM

ODM’s unity is now under test. Edwin Sifuna, the party’s Secretary-General, has called for calm. “I will not be the one to break ODM,” he told mourners in Bondo. “Our late leader wanted a united Kenya — we must not betray that dream.”

However, Sifuna’s stance faces internal resistance. Governor Wycliffe Oparanya and former Mombasa Governor Hassan Joho are pushing for stronger cooperation with Ruto’s administration, arguing that political inclusion could unlock more national projects in ODM regions.

“Raila’s last political act was joining government,” said Joho. “That tells us where his mind was — on unity and development, not division.”

But not everyone agrees. Ruth Odinga, the late leader’s sister and Kisumu deputy governor, insists ODM must remain a watchdog. “My brother never sold out his principles,” she said. “ODM must protect democracy, not become an echo of power.”

Declining Numbers, Rising Risks

With 6.1 million registered members, ODM remains Kenya’s largest opposition-turned-coalition party. Yet its influence appears to be slipping. A recent Infotrak poll shows ODM’s support dropped from 38% in 2024 to 29% in 2025. Analysts say this trend could accelerate if factionalism deepens.

“ODM has to transform into a modern party, not a personality cult,” observed Dr. Jane Thuo, a political sociologist. “Otherwise, it risks losing its reformist DNA.”

Ruto’s Balancing Act

President Ruto, who attended Odinga’s funeral, praised his late rival as “a patriot who sacrificed for the nation.” He vowed to preserve Odinga’s legacy through continued inclusion.

“I will protect ODM’s unity,” Ruto said. “Our government will ensure that the ideals Raila stood for continue to guide Kenya’s political stability.”

Insiders say the president views ODM’s survival as crucial to his coalition’s legitimacy ahead of the 2027 General Election. However, some advisers warn that empowering ODM too much could create a parallel political center within his own alliance.

A senior source in the presidency told Reuters that “Ruto’s priority is to prevent ODM from fragmenting, but not to let it become an alternative power pole.”

Global Reactions and Democratic Stakes

The United States and the European Union have lauded Odinga’s contributions to Kenya’s democracy, urging leaders to uphold pluralism. Western diplomats emphasize that a strong ODM ensures checks and balances within Ruto’s unity framework.

“The broad-based government should not silence dissent,” said an EU envoy in Nairobi. “ODM’s vibrancy keeps Kenya’s democracy alive.”

Analysts estimate the 2025 by-election cycle and internal party elections will cost ODM about KSh 1.2 billion ($8.7 million) — a process that could define whether the party modernizes or fractures.

A New Era Without Its Founder

For now, ODM stands at a historic junction. Will it become Ruto’s strongest ally — or rebuild as Kenya’s main opposition force?

As one mourner in Bondo put it, “Raila may have died, but ODM is still breathing. Whether it walks or crawls from here is up to those he left behind.”

Regional Security & Peacebuilding

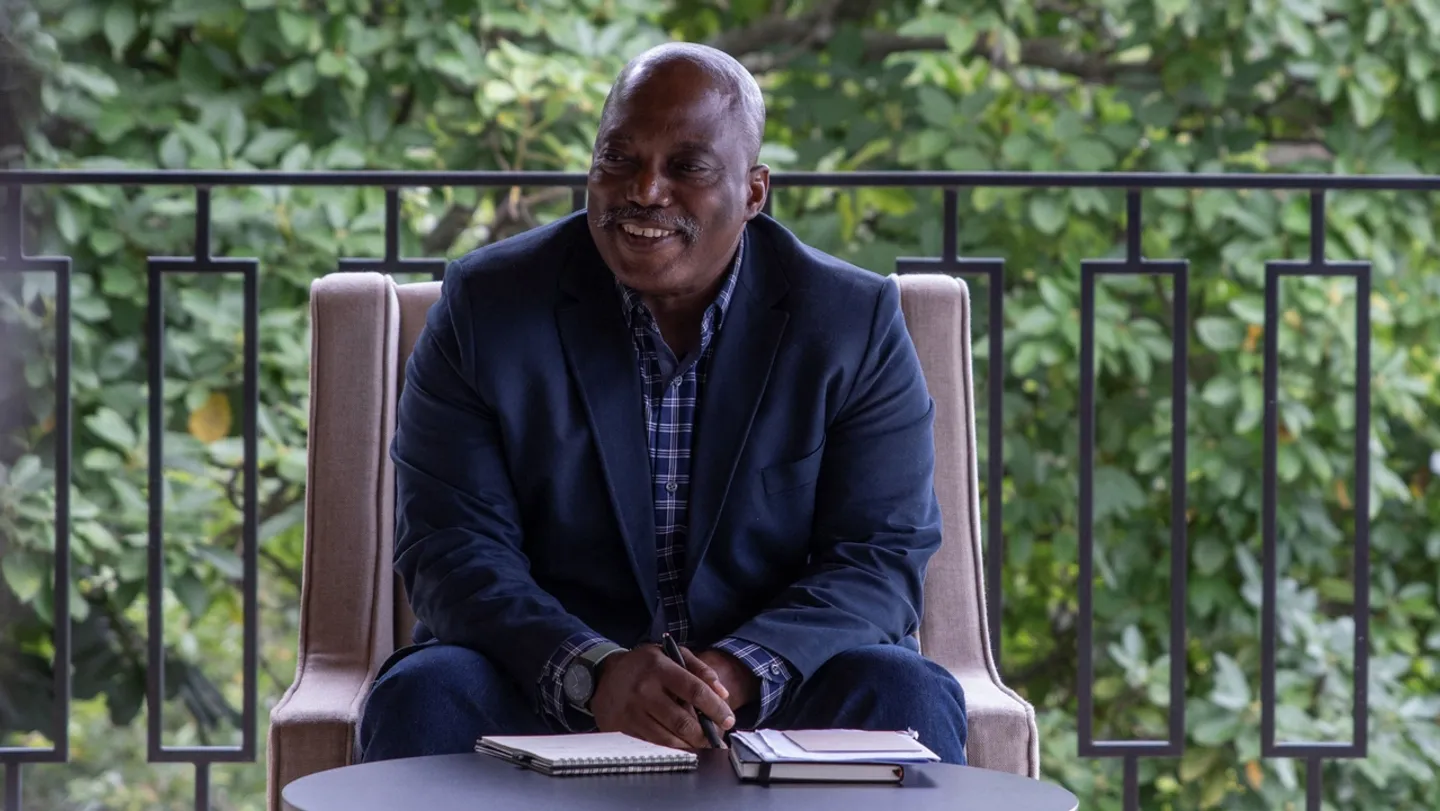

Kabila’s Nairobi Meeting Deepens DRC–Kenya Rift

Kenya faces diplomatic pressure after hosting a meeting of Congolese opposition figures led by Kabila.

Joseph Kabila’s Nairobi appearance sparks diplomatic tension as Kinshasa and Nairobi navigate political and regional stakes in Central Africa.

Kinshasa Condemns Kabila’s Political Re-Emergence

The former president of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Joseph Kabila, re-emerged publicly in Nairobi for the first time since his death sentence in absentia on treason and war-crimes charges. The surprise gathering, held in Kenya’s capital, brought together more than a dozen Congolese opposition leaders who announced the creation of a political front aimed at “restoring democracy” and “ending tyranny” in the DRC.

The Nairobi conclave further escalates diplomatic tensions between the two African states.

Kinshasa reacted sharply. Deputy Prime Minister for Interior and Security Jacquemain Shabani described the Nairobi event as a “black mass organised by convicted criminals against our country.” He said the government would “take action against the actors and initiators of this meeting if it is proven to be preparing to destabilise the institutions of the republic.”

Government spokesman Patrick Muyaya added that Kabila’s actions undermine sovereignty and could “reignite conflict” in an already volatile region. The government’s official line remains that Kabila’s sentence—handed down on 30 September 2025 by a military court—is legally binding and reflects his alleged links with the M23 rebel group.

Kenya Walks a Diplomatic Tightrope

Kenya’s response has been measured but telling. Officials at the Ministry of Foreign and Diaspora Affairs confirmed awareness of the meeting and provided routine security for participants. However, the ministry declined to comment on the political nature of the gathering, emphasising Kenya’s policy of “non-interference in the internal affairs of friendly nations.”

A senior diplomat quoted by The East African said Nairobi views such meetings as legitimate so long as they promote dialogue rather than armed conflict. Yet analysts warn that even this neutral posture could strain bilateral ties, given Kinshasa’s accusations that Kenya hosts rebel sympathisers.

Kenya has invested heavily in peace mediation across the Great Lakes region, from Sudan to South Sudan and Somalia. The optics of sheltering a former president convicted of treason threaten to blur Nairobi’s image as a regional stabiliser.

Who Is Joseph Kabila?

Kabila rose to power in 2001, at just 29, following the assassination of his father, President Laurent Kabila. He ruled until 2019, steering Africa’s second-largest country through two wars but facing persistent allegations of corruption, repression and electoral manipulation.

His decision to postpone elections beyond his constitutional term in 2017 sparked widespread unrest. When Félix Tshisekedi finally took office in 2019, it marked the first peaceful transfer of power in Congo’s post-colonial history.

Despite stepping down, Kabila retained significant influence through his party, the People’s Party for Reconstruction and Democracy (PPRD), and loyalists within the military and security services. His recent re-emergence revives long-simmering fears that he still commands covert networks in the DRC’s mineral-rich east.

In February, Kabila authored an op-ed in South Africa’s Sunday Times where he denied working with rebels but expressed sympathy for what he called their “struggle against oppression.”

Regional Stakes and the Great Lakes Equation

The DRC’s eastern provinces remain one of the world’s most unstable conflict zones. Armed groups, including M23, operate amid competition for control of cobalt and gold—minerals vital to global technology supply chains.

Kabila’s reappearance in Nairobi touches regional nerves for four key reasons:

- Sovereignty and Security: Kinshasa sees the meeting as a potential attempt to coordinate rebellion from abroad, threatening fragile national cohesion.

- Diplomatic Optics: Kenya, as an East African Community (EAC) member, faces the challenge of reconciling its openness with security sensitivities of partner states.

- Peacebuilding Pressure: Nairobi hosts the EAC-led Nairobi Process on Eastern DRC. Hosting Kabila could undermine its credibility as a neutral broker.

- Economic Interests: Kenya’s banks and logistics firms, including Equity Bank and Kenya Airways, are expanding in the DRC under EAC integration frameworks. Diplomatic strain could chill this growth.

Regional and Global Repercussions

The crisis tests the balance between democratic freedoms and regional diplomacy. Analysts at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) warn that renewed political instability could jeopardise multibillion-dollar infrastructure and energy projects linking Kenya, Uganda and the DRC.

Western governments, including the United States, have called for restraint, urging Kenya and the DRC to use dialogue channels to defuse tensions. The African Union likewise appealed for calm, reminding members of their obligations to respect sovereignty while protecting political freedoms.

What Comes Next

Observers are watching to see whether Kinshasa files a formal diplomatic protest or seeks Kabila’s extradition. Kenya may soon clarify its stance on hosting political exiles to protect its regional mediation role.

If Kabila’s movement gains traction among exiled politicians and diaspora communities, it could reshape Congo’s political landscape ahead of future elections. For now, Nairobi finds itself uncomfortably positioned at the crossroads of regional diplomacy and continental intrigue.

-

Politics, Governance & Regional Affairs6 days ago

Politics, Governance & Regional Affairs6 days agoRaila Odinga’s Death Tests ODM Unity

-

Celebrities, Creatives & Public Figures7 days ago

Celebrities, Creatives & Public Figures7 days agoCaptain John Kiniti: Kenya’s First African Pilot

-

Regional Security & Peacebuilding7 days ago

Regional Security & Peacebuilding7 days agoKabila’s Nairobi Meeting Deepens DRC–Kenya Rift

-

Banking, Finance & Economic Policy4 days ago

Banking, Finance & Economic Policy4 days agoMacharia to Lead Sidian Bank’s Revival

-

Celebrities, Creatives & Public Figures5 days ago

Celebrities, Creatives & Public Figures5 days agoWPP-Scangroup Names Owusu-Nartey as CEO

-

Banking, Finance & Economic Policy6 days ago

Banking, Finance & Economic Policy6 days agoKenya Banks Poised for Strong Q4 Rebound

-

Human Rights & Social Justice7 days ago

Human Rights & Social Justice7 days agoRwanda Targets Exiled Critics with Sanctions

-

Banking, Finance & Economic Policy5 days ago

Banking, Finance & Economic Policy5 days agoEthiopia Caps Foreign Bank Ownership at 49%